We can’t always know what’s really going on in the world at any given moment. To accommodate this fact, we rely on a mental map. Built over many years, we use it to fill in the blanks where we can’t know what is happening. We use it to approximate what we expect is happening.

That button in the lift? When we press it, our mental model tells us we triggered the door to close, but there’s a very good chance that the button does nothing at all. That thermostat in your office? Many of them are fake.

What does our model expect to happen when a researcher demonstrates a Covid-19 therapeutic is available and effective? As ever, shares are much appreciated.

On the 24th of February 2020, just four weeks after the word ‘SARS-CoV-2’ entered the global consciousness, researchers in China led by Jia Liu, sent a paper to nature.com called “Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro”. The world needed a solution, and researchers had found a very promising treatment that was widely available and well understood. The study was published on March 18th.

“In conclusion,” the authors said, “our results show that HCQ can efficiently inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. In combination with its anti-inflammatory function, we predict that the drug has a good potential to combat the disease.”

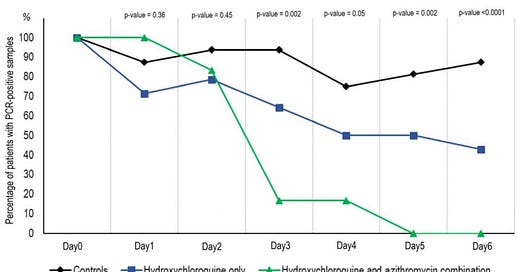

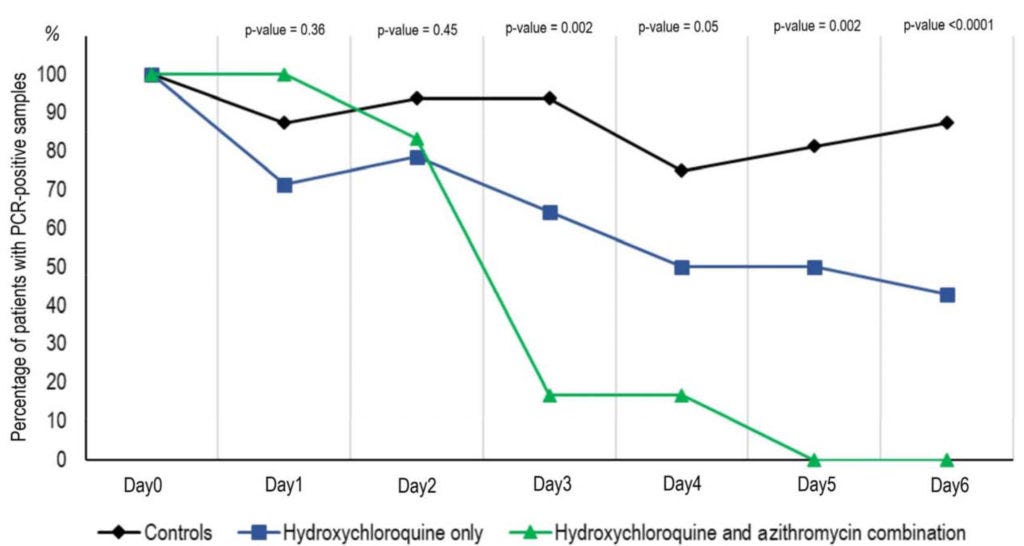

It wasn’t the first study suggesting this. The body of research had caught the eye of a team of researchers in Marseille, France. Led by Professor Didier Raoult, they had a study looking at hydroxychloroquine ready and registered by March 5th 2020. By the 18th of March, we had results, and they looked great. As the days progressed, Covid-19 patients taking hydroxychloroquine were recovering significantly faster.

None of this was surprising to the researchers close to the subject matter. Chloroquine had already been identified as a treatment for the original SARS virus all the way back in 2006. To paraphrase the researchers behind that study, in March 2020 they too were telling us, “we expect this drug is going to work.”

We now knew the pandemic was caused by a virus very closely related to SARS, so hydroxychloroquine was an obvious choice. To sure things up, Professor Didier Raoult and his team had demonstrated the drug worked in humans. Its safety profile was well understood, it was highly available, and cheap at just $13 per day. Professor Didier Raoult shared his paper and presented his findings on YouTube.

This good news story soon soured. Professors turned up out of nowhere to make comments on the research. One was Professor Gilles Pialoux, an infectious disease specialist at Tenon Hospital. He told Medscape's French Edition: "The idea is interesting but we need large, randomised, controlled trials. We should not communicate this kind of information on YouTube, it is not meaningful.”

In Science parlance, that’s a major putdown, but Pialoux wasn’t done. It was time to shoehorn in the research he’s working on. "Don’t forget”, Pialoux said, “this compound has not been included in Inserm’s trial because there are more interesting avenues, such as remdesivir or Kaletra.”

Remdesivir eh? We’ll return to that later.

Undeterred, Professor Didier Raoult continued to publish more data, and soon enough he had three studies published in the literature. They all showed the same positive results. Two of those studies had control groups, but the biggest study Raoult published was a retrospective study. Enter Xavier Lescure, an infection specialist at Bichat hospital, who briefed a French TV channel, “Any study without a control group does not show anything at all.”

That’s two black eyes for Raoult.

The attacks were stacking up. If the aim was to discredit the findings, the endless attacks had worked perfectly. What should have been a good news story was memory-holed as the “controversial coronavirus drug”. The whole process took less than four weeks. But it’s all ancient history now. No matter.

Hydroxychloroquine wasn’t widely adopted, and our model of the world tells us that it must be because some smart people in important jobs carefully assessed the data and concluded it didn’t work. But my model isn’t what it once was. I can now see a pattern, and my model tells me something is up. A Professor had shown that a cheap generic drug was effective against a disease which stood to make the pharmaceutical industry billions of dollars. Rather than welcome the finding, he was attacked.

One model fills in the blanks, “well Raoult must have been dead wrong or else we’d have used the drug widely”. But an updated post-covid model wonders if those attacking Raoult had skin in the game. With a hypothesis in hand, I did what amounts to the most basic of research. Something that all of the journalists who ‘foghorned’ those Professors should have done.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Digger to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.