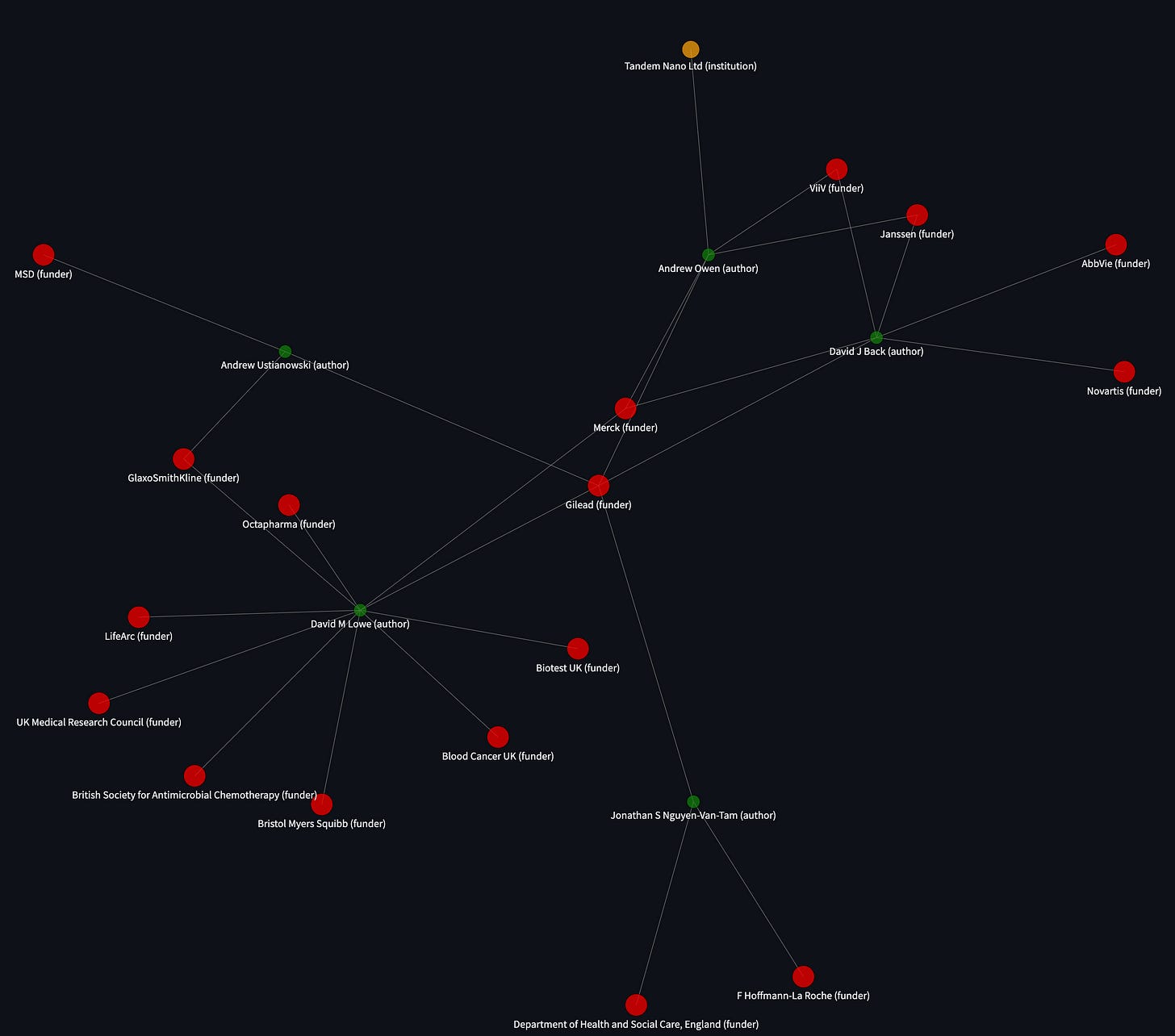

Seeing the network of influence

AI is opening up a new frontier in measuring industry meddling

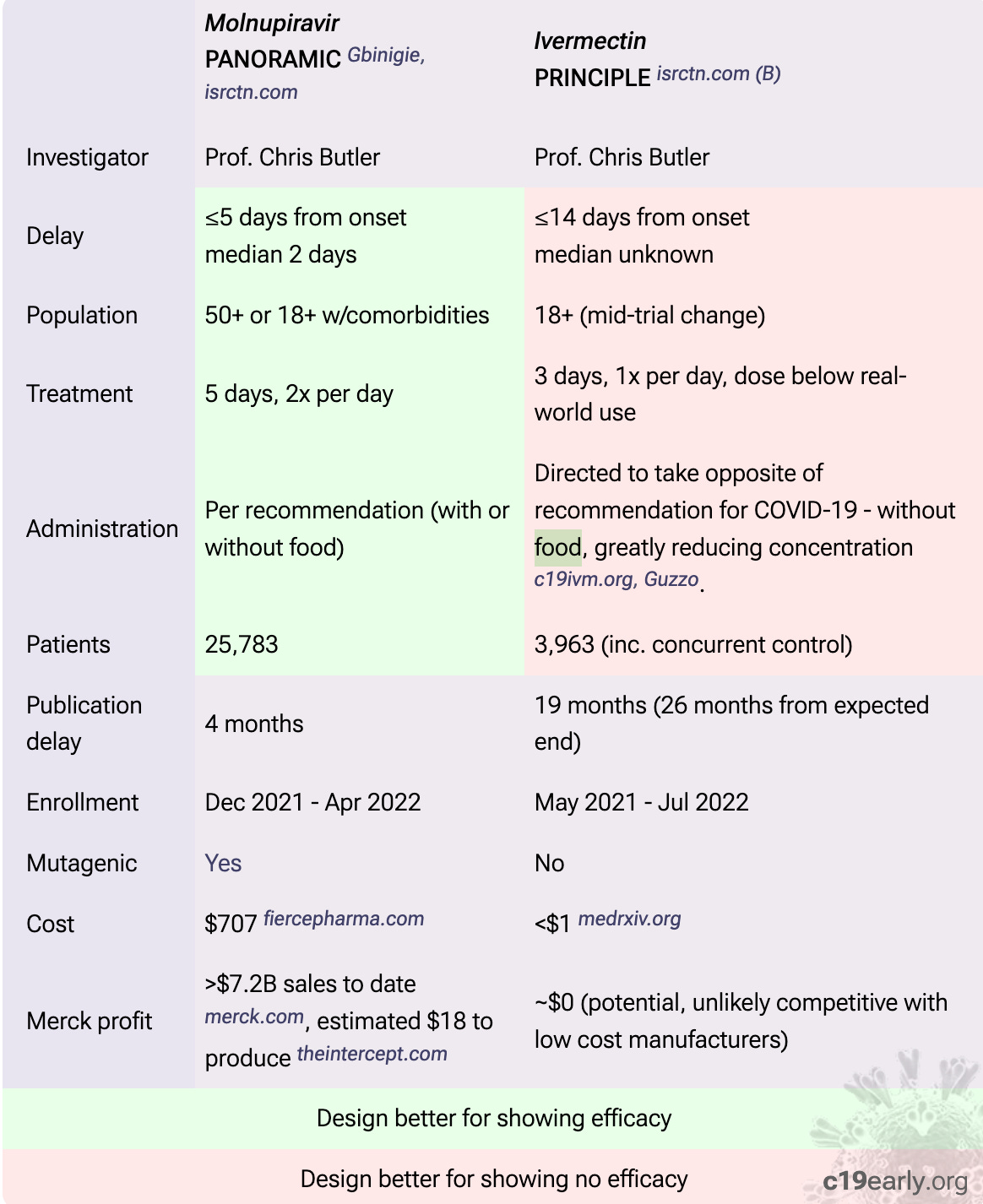

Last week we looked at the curious differences between a study investigating an industry ‘darling’ drug, and a study looking at Ivermectin. Predictably, there were huge advantages baked into the design of darling drug’s study. CV19early did a great job showing how the scales get stacked so it’s worth repeating the graph. The two drugs had the same principle investigator but totally different approaches to investigating the drugs. Which of these two studies will demonstrate the drug’s effect? The study where the drug was used quickly, with a proper dose, on a population of people who would benefit from it, or the study where the exact opposite happened?

Many epidemiologists and health policy wonks seem entirely disinterested in the network of pharmaceutical cash that tip the scales of the studies in their favour. Under this perspective, the gravity of ‘medicine’ shines a bright impenetrable light. Medical science is a squeaky clean and noble discipline. “They wouldn’t nudge the data in their favour! These are scientific people!” They’re often seduced by sophisticated trial designs and the apparent prestige of the ‘high impact’ (ignore Surgisphere) sunny uplands of medical publishing. But journalists…. we like to follow the money.

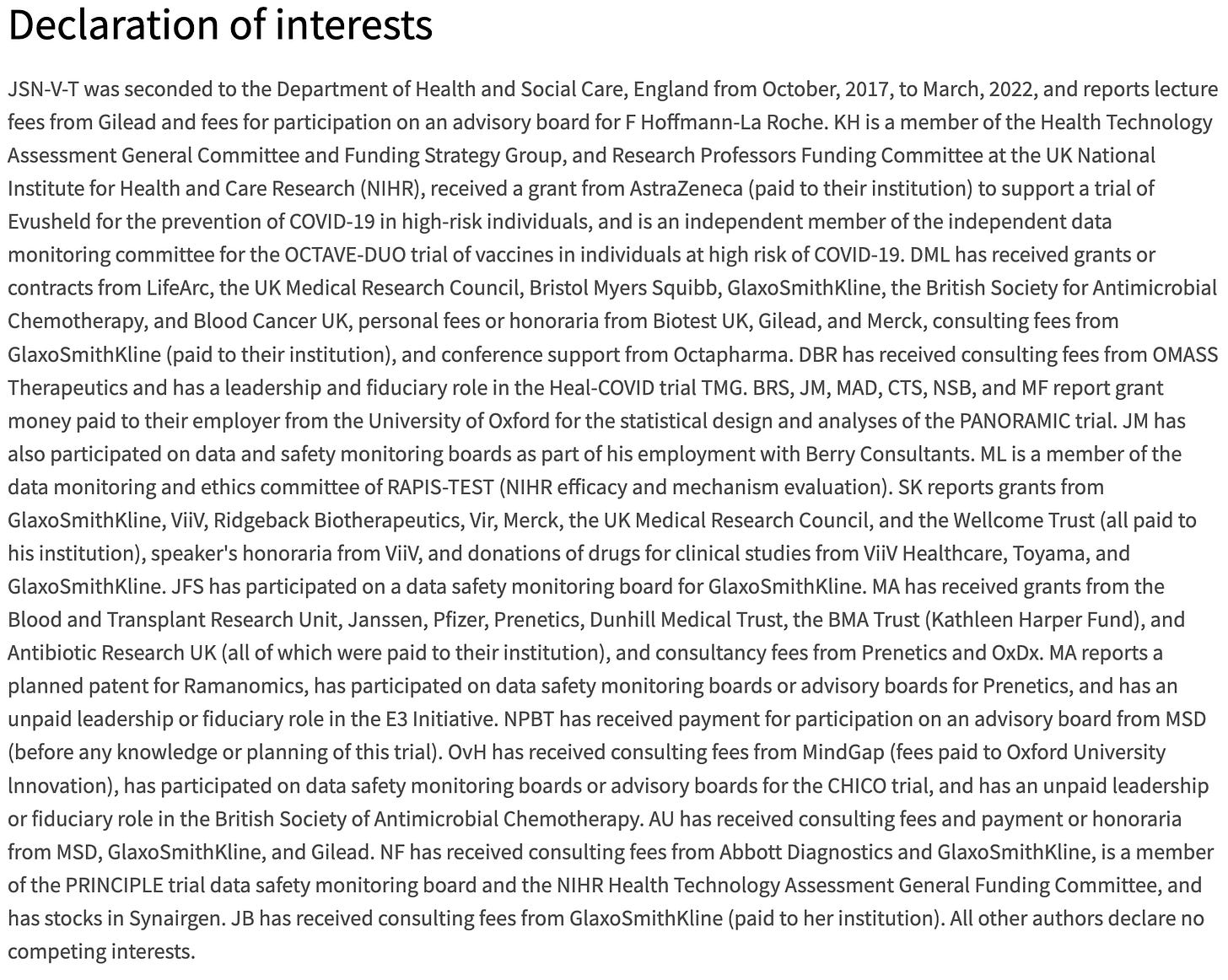

Paper by paper, it’s hard to get ‘a sense’ of just how much sway the industry has over the medical publishing world. We can be somewhat thankful that in the UK at least, papers do often contain a conflict of interest section, but they’re a bit like those people who pay $212 fines in pennies. The conflict of interest section is deliberately designed to frustrate you, it creates more work than it’s worth to properly analyse.

It’s not that the “John Doe of McMaster University received money from Pfizer”, it’s that JD received research grants from Pfizer. The tiny bit of obfuscation matters, because it means you need to manually match up the initials to the author, and it’s a laborious and boring task. At best you might be able to do it for a handful of papers, but it’s thankless work. This tiny innovation, of hiding names behind obscure initials, stops machines from parsing the information, storing it, and analysing it.

Until today.

Take the molnupiravir study we looked at last time, above is a screenshot the Declaration of Interests section. It’s fairly typical of UK papers publishing on new drugs or pharmaceutical products. Do you want match those initials up to the paper's authors? No, you don’t, and that’s exactly the way the industry likes it, but AI loves jobs like this. It can take this one paper and turn it into a machine readable JSON document. It’s the same paper, but because machines can now read it, we can see it. Special interests can now be plotted out at the funder level, the institution level, or the author level.

Here’s the result, using data from just three papers, including this one. What this means is that papers could now be searched via their funders. Research topics could be filtered by topic, and then ‘exclude papers with industry sponsored research’. You could do research in which you gathered up all the industry influenced papers on a certain topic, and you compared with with all the papers that don’t have those same influences. What do you think we might find if such a platform existed?

In the above graphic, based on no more than three papers, we can see that Gilead has a small network of authors in the UK, including Sir Jonathan Stafford Nguyen Van-Tam who became a Deputy Chief Medical Officer for England on 2 October 2017. At the time these papers were published, Van-Tam was acting as a public servant in the UK government. Whilst he was advising government on medical policy, he’s sitting on the advisory board of La Roche, and he was getting lecture fees from Gilead. This is all declared in various publications, but seeing the data this way makes it trivial to see the connections in the UK medical publishing world, and it starts to look very different to the ‘white coat lab nerd’ image it has thus far enjoyed.

This is buildable right now. With just three papers, the dataset is already interesting and helpful in gathering insights about pharmaceutical influence on the medical publishing industry. The issue isn’t the build, it’s in navigating the GDPR laws involved in having to store this in a database. Are there any good legal people on Substack who might take an interest in this? Are there any open data and transparency campaigners who might take an interest and offer some insights on this? For now, the bare bones prototype of this system is live and ready for viewing here:

Make the visualisation full screen, click and drag around a cluster that looks interesting, then double click to return to a birdseye view. You can search by funder, and DOI from science paper, though, as I said… there’s only three papers in the dataset.

I have many many things that need building, writing, investigating and developing both on The Digger and case.science. The medium term plan is to have this prototype working at scale on case.science so each body of data will also come with a network graph of funders. As you can imagine, this takes a lot of work, and right now both case.science and The Digger are run entirely by myself. If you like the look of the work that’s happening here, please support it with a subscription and a share.

Precisely why I won't label AI good or evil. I consider it a way to process information. There are many constructs that do so. Just a matter of intent and the possibility of misuse - either intentional or inadvertently.

Great work, Digger! I can see applications of this in a 'panocracy' that I'm working on myself.

This, and your case.science project, is exactly the kind of AI that will help put control of our lives back where it belongs - to us.